At the last PHPDublin meetup I was asked «What do you do?» and as usual the answer boiled down to «I design and build event sourced applications». Which leads to the following question. «What is Event Sourcing?».

That’s where this article came from, it is my best shot at explaining Event Sourcing and all the benefits it brings.

The Status Quo

Before we get into the nitty gritty of event sourcing, let’s talk about the status quo of web development.

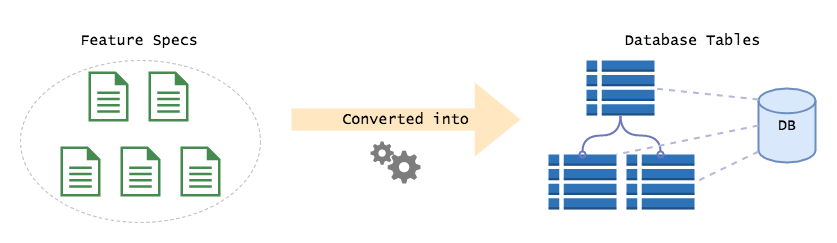

At it’s heart, current web dev is database driven. When we design web apps, we immediately translate the specs into concepts from our storage mechanism. If it’s MySQL we design the tables, if it’s MongoDB, we design the documents. This forces us to think of everything in terms of current state, ie. «How do I store this thing so I can retrieve (and potentially change) it later?».

This approach has three fundamental problems.

1. It’s not how we think

We as a species do not think or communicate in terms of state. When I meet you for a coffee and ask «What’s happening?», you don’t tell me the current state of the world and then expect me to figure out what’s changed, that would be insane.

«Well, I have a house, a car, a refrigerator, three social media accounts, a cat, a pain in my right foot, the crippling self-doubt that I’m terrible at conversations, another cat …etc»

See what I mean? That’s crazy. In reality you’d tell me the new things that have happened since we last talked, and from that I’m able to figure out how your world looks now. In short, you tell me a story, and a story at it’s simplest is a sequence of events.

2. Single data model

In the above we use the same model for both reads and writes. Typically we’d design our tables from a write perspective, then figure out how to build our queries on-top of those structures. This works for well small apps, but becomes problematic in large ones. You see, it’s next to impossible to build a generic model that is optimised for both reads and writes. As the system grows, the queries will get more and more complex, eventually hitting a point where every query contains 10 joins and is 100 lines long. This soon becomes unmaintainable, brittle and expensive to change.

3. We lose business critical information

This is a big one. With a standard table driven system, you’re only storing the current state of the world, you have no idea how your system got into that state in the first place. If I were to ask you «How many times has a user changed their email address» could you answer it? What about «How many people added an item to their cart, then removed it, then bought that item a month later»? That’s a lot of useful business information that you’re losing because of how you happen to store your data!

Event Sourcing

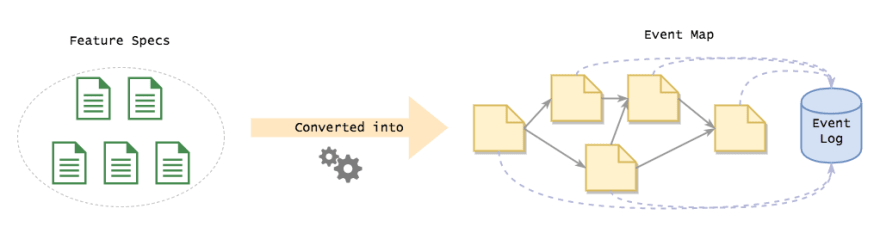

Event Sourcing (ES) is opposite of this. Instead of focussing on current state, you focus on the changes that have occurred over time. It is the practice of modelling your system as a sequence of events.

Let’s give an example. Say we have the concept of a «Shopping Cart». We can create a cart, add items to it, remove them, and then check it out.

A cart’s lifecycle could be modelled as the following sequence of events:

| Event |

|---|

| 1. Shopping Cart Created |

| 2. Item Added to Cart |

| 3. Item Added to Cart |

| 4. Item Removed from Cart |

| 5. Shopping Cart Checked-Out |

And there we go, that’s the full lifecycle of an actual cart, modelled as a sequence of events. That is Event Sourcing. Simple huh!

Pretty much any process can be modelled as a sequence of events. Infact, every process IS modelled as a sequence of events. Talk to a domain expert, they won’t talk about «tables» and «joins» (unless you’ve indoctrinated them into tech concepts), they’ll describe processes as the series of events that can occur and the rules applied to them.

How do you enforce business rules?

Most business operations have constraints, a hard rule that cannot be broken. In the above, a hard rule would be «An item must be in a cart before it can be removed». You can’t remove an item if it was never added to the cart, that sequence of events should never happen. So to enforce this constraint, you need to answer the question, «Does this item exists?», how do you do that without state?

Turns out this is easy, you just need to check that an «Item Added to Cart» event has happened for that item, then you know the item is in the cart and that it can be removed. Business rule enforced.

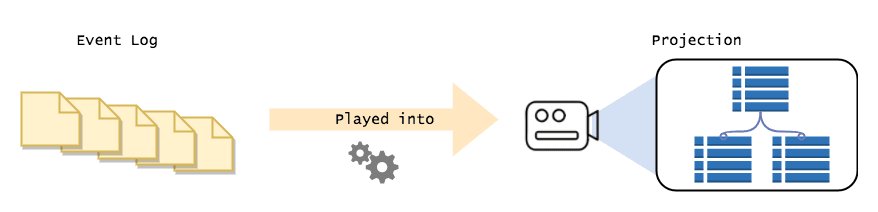

This is how you answer every question about state in an event sourced system, you replay a subset of the events to get the answer you need. The is usually called projecting the events, and the end result is a «projection».

Isn’t this expensive and time consuming?

Not at all. To enforce constraints, you typically only need the tiniest subset of events. Fetching the useful history of a concept, such as a Cart, is typically a single database call. You load the events and replay them in memory, «projecting» them, to build up your dataset. This is lighting fast, as you’re doing it on the local processor, rather than making a series of SQL calls (network calls are insanely slow compared to local operations, by at least two orders of magnitude!).

What about showing data to the user?

If every piece of state is derived from events, how do you fetch data that needs to be presented to the user? Do you fetch all the events and build the dataset each time?

The answer is no, you don’t, that would be ridiculous.

Instead of building it on the fly, you build it in the background, storing the intermediate results in a database. That way, users can query for data, and they will get it in the exact shape they need, with minimal delay. In effect, you cache the results for later use.

Now, this is where things get really interesting. With ES, you are no longer bound by your current table structure. Need to present data in a new shape? Simply build up a new data structure designed to answer that query. This gives you complete freedom to build and implement your read models in any way you want, discarding old models when they’re no longer needed.

The benefits

We’ve looked at a few of the benefits all ready, but lets go deeper, because believe me, this style of development offers a host of benefits that I can no longer live without.

1. Ephemeral data-structures.

Since all state is derived from events, you are no longer bound by the current «state» of your application. If you need to view data in a new way, you simply create a new projection of the data, projecting it into the shape you need. Say bye-bye to messy migration scripts, you can simply create a new projection and discard the old one. I honestly cannot live without this anymore, this alone makes ES worthwhile.

2. Easier to communicate with domain experts

As I said before, domains experts don’t think in terms of state, they express business processes as a series of events. By building an event sourced system, we’re modelling the system exactly as they describe it, rather than translating it into tech concepts and losing information. This makes communication a lot smoother, we are now talking in their language and this makes all the difference when writing software.

3. Expressive models

Event Sourcing forces you to model events as first class objects, rather than through implicit state changes (ie. changing a value in a table). This means your models will closely resemble the actual processes you’re modelling. This brings a lot of clarity to the table and stops you getting lost in the details of your storage technology. It makes the implicit explicit.

4. Reports become painless

Generating complex business reports becomes a walk in the park in an event sourced system. You have the full history of every event that has ever happened, in chronological order, this means you can ask any question you like about that data historically.

Think of the power of this! Take the earlier example, you want to know how many users removed an item from their cart and then bought it a week later. In a standard web app this would take weeks of development, and once it’s released, you have to wait for the data to populate before you could generate the report. With an ES system, it’s built in from the get go, so you can generate that report right now. You could also generate the report for any previous point in the time. In other words, you have a time machine.

5. Composing services becomes trivial

In standard web dev, plugging two systems together is usually quite tricky, and it frequently leads to tight coupling. ES solves this problem by letting services communicate via events. Need to trigger a process in another service when something happens? Write an event listener that runs whenever that event is fired. This allows you to add new integrations/functionality, without having to modify existing domain code.

For example, say you want to send a welcome email when someone registers. Instead of modifying core registration code, you would simply create an event listener for the «User has Registered» event, which then triggers an email through some external service. Simple.

6. Lightning fast on standard databases

You don’t need to use a fancy database to store your events, a standard MySQL table will do just fine. Databases are optimised for append only operations, which means that storing data is fast, while modifying data is slow. This is why ES works so well with current tech, events are append only.

7. Easy to change database implementations

Due to the ephemeral nature of event sourced data-structures, you now have full freedom to use any database technology you like to store state. This means you get to choose the best tool for the job. And If you find a better tool, and you can switch to it at any point, there is zero commitment. This gives you an incredible amount of freedom. Case in point, we’re currently moving some of our more complex projections from MySQL to OrientDB, and so far it’s been a breeze.

The issues

Like anything, ES is not a free lunch. Here are some of the surprises you will run into.

1. Eventual Consistency

An ES system is naturally eventually consistent. This means that whenever an event occurs, other systems won’t hear about it immediately, there is a short delay (say ~100ms) before they receive and process the event, gaining consistency. This means that you can’t guarantee that the data in your projections is immediately up-to-date. This sounds like a big deal, but it really isn’t. Modern web dev apps built on ReactJS will build up state from actions as the user performs operations, so having a query side that’s lagging a few milliseconds is a non issue.

TBH, this is actually a blessing in disguise. Eventually consistent systems are fault tolerant and can handle service outages. If you’re building a distributed app using a micro-service or serverless architecture, it needs to be eventually consistency to be stable.

2. Event Upgrading

Events will change shape over time, and this can be a bit tricky to handle if you don’t plan for it in advance. When an event changes shape, you have to write an upgrader that takes the old event and converts it into the new one. This is done on the fly when you read the events from the store. Think of them as migrations for your events. Not as difficult as it sounds, just have a strategy in place for upgrading events and you’ll be fine.

3. Developers need deprogramming

The status quo in web dev is state driven development, this means developers will immediately jump to thinking in tables, rather than events. I’ve found it takes time to «deprogram» developers, they need to unlearn all the bad habits they’ve picked up. This usually manifest as events that are pure CRUD and don’t mirror the domain language. The best way to combat this is to pair new developers with experienced ESers.

Conclusion

There we have it. At this stage it should be clear that I love event sourcing. It solves all the big problems our team has faced when building large scale distributed business software. It allows us to talk to the business in their language, and it gives us the freedom to change and adapt the system with ease. Throw in built in business analytics and you’ve got a winning combination. There is a learning curve, but once you get into Event Sourcing, you’ll never want to look back, I know I don’t.